Brexit was everywhere

In 2018 and 2019 here in Europe the Brexit was in the forefront of our consciousness. Not a day went by that there wasn’t a Brexit article in the newspaper, and often there were two or three. The young and cosmopolitan wanted to stay in the European Union. The old and island-oriented wanted out. It’s a tale of urbanisation, of moderns empires, of generations, of social classes… It has been called a Greek tragedy.

You may remember how the Brexit advocates were quite surprised when they won. The victors were more confused than the losers. Suddenly they were burdened with a responsibility for what they wanted the UK to go towards, specifically. They had been thinking mostly of where they wanted the UK to move away from. Their ideas about what to move towards were vague (Make the British Empire Great Again!). Nigel Farage of the UKIP was facing an existential crisis, when the only reason for UKIP’s existence, getting out of the EU, was actually achieved.

In one sense the Brexit was beautiful

First of all, let me mention a frame that – to my surprise – was totally absent from the discussion. Here we had an empire, called the European Union, where one of the major provinces – the UK – wanted to leave. And there was not the faintest hint of war. A huge area left the empire by democratic means. Caesar would have sent the legions. Napoleon would have returned from Russia. Hitler would have tripled the Luftwaffe. And all the European leadership did was pout and say it was a challenge for Europe. I thought that was beautiful, historically speaking. If I were British, this response alone would be a reason for me to remain in the EU.

Leave and remain mindset

So let’s have a look at the Brexit mindset. What were the values and thinking styles that distinguished ‘remain’ from ‘leave’? Leave said: Britain will do fine on its own, it will gain back its position as one of the great world powers. The Empire will rise again. Remain said: Let’s stay in the bigger system, it will provide safety in numbers. Leave said: Britain will be free to manoeuvre without EU regulations, therefore it will prosper economically, negotiating new treaties that are UK oriented rather than EU oriented. Versus remain saying: Hello?!? Britain has a 400 billion export to the EU, hampering that will cost us more than any flexibility will gain us. And then there was immigration. Leave said: Leaving the EU will give us back control of our borders. No more Polish workers taking our jobs. No more Syrian refugees taking our housing. Remain was saying: Even apart from doing the right thing towards the refugees, Brits could lose the freedom to travel, study, live and work in the other 27 EU countries.

What followed were negotiations with the EU. They were very difficult because prime minister May seemed to be approaching them – even though she was originally against the Brexit – from the same mindset that started the Brexit. The EU should stop harassing us and give us what we, as a great and successful empire are entitled to. The orange argument was – almost – : ‘We understand that there are some rules, but rules are for ordinary countries, not for empires like us’.

In Graves terms that was an ‘orange’ argument: the really important like us make their own rules. The orange motivational drive is about being the best, about victory and success. It fits very well with the British myth of returning to being a Great Empire. The Northern Irish Republic met with this same attitude when they refused the British ‘backstop’ arrangement (avoiding a hard border). A conservative former minister was quoted saying ‘We simply cannot tolerate the Irish treating us like this. They … really need to know their place’.

If Britain – as a nation – had filled out MindSonar, their criteria would have looked something like this:

Criteria (Sorted)

- Success versus Safety

- Flexibility versus Togetherness

- Profit versus Morality

- Honour versus Pragmatism

Meta criterion: Autonomy versus Being part of

Graves Drives

From these criteria we can project the Graves motivational categories. On the leave side we see success, flexibility and profit. That all sounds very orange, doesn’t it? It’s all about winning. About being the best. ‘We don’t need you guys, we can win this on our own. We are competent and we are confidently facing the competition’. And there’s some red in there too: ‘Who the f**k are you to tell us what to do? We’re boss here’. So the leave side sounds very orange and red. B.t.w. these are both individual motivational drives. And also b.t.w., these values are not unique for Brexit, they can be found in almost any populist movement.

The ‘stay’ criteria are about safety, togetherness and morality. What Graves colours does that bring to mind? Right, blue and green. We ought to help the refugees. It’s the right thing to do. Based on international law they are entitled to our protection. We will be rewarded eventually for being part of a powerful group (blue). And we want to be together. Together we’re stronger. Everybody should be heard. Green. Blue and green, are both motivational drives that focus on the group.

Brexit is a battle between red/orange and blue/green. It’s no great surprise that the leave camp fell apart after the victory. They weren’t that together in the first place. And many of the responses of the winning politicians were quite red: ‘I don’t think he should lead the country, I am much better suited!’

Something else we could predict, unfortunately, is that the great environmental issues (global warming, sustainable energy, natural farming) would also lose terrain in Britain. The blue drive cares about what ought to be done about the environment. The green drive cares about what we might find ourselves in together. But the orange drive cares only about winning and the red drive cares about power.

Specific versus general away from arguments

Both camps used both towards arguments (where we want to go) and away from arguments (what we want to avoid). The leave camp used away from arguments like ‘We are paying the EU too much’, ‘We have to adhere to such-and-such absurd EU regulations’, and so on.

Many stay arguments were away from too: ‘Our economy will suffer’, ‘Our geopolitical position will be weakened’, and so on.

However the type of away from arguments were different. A good example was the ‘close the border’ argument of the leave camp: ‘We’ ll be overrun by thousands upon thousands of immigrants and refugees, taking our jobs and eating up our resources’. This is a graphic and specific image. My British friend Graham Dawes explained that the newspapers had played an important role in de Brexit discussion. They were painting a picture – and showing photographs – of hordes of immigrants in Calais, waiting to swarm the UK, sucking the country dry of jobs, health care and housing. They kindled the fears of the British people, using endless repetition. ‘Sensations sells’.

The counterargument of the remain camp was: ‘We don’t want to violate the international laws regarding refugees’. This is a very general image, looking quite pale in comparison to the threatening refugee hordes. The legal argument conjures up images of dusty law books and complicated texts.

And of course there is the ‘absurd Brussels regulations’ argument, also ‘away from’. Like the ban on large vacuum cleaners to force consumers to use less energy. Boris Johnson was actually waving a vacuum packed fish, explaining how unhappy the fish merchants were about the European packaging rules. Justifying regulations like these, by the stay camp, was counterintuitive and complex. Mocking these regulations was simple and entertaining. Brexiteers often spiced up their arguments with examples like the vacuum cleaner rule.

All in all, we can say that the Brexiteers had many quite specific away from arguments (f.i. specific ridiculous EU rules or specific jobs lost to immigrants). The Remainers had more general away from arguments (f.i. defaulting on international laws regarding fugitives or losing citizen rights in the EU). In the public debate, this was a clear disadvantage for the remain camp.

Specific versus general towards arguments

If we look at the towards arguments we saw a mirror image of the away from arguments. The Brexiteers had the advantage of towards arguments about things that hadn’t happened yet. It was quite doubtful that they would ever happen, but as arguments and images in the public debate they were strong. All these arguments were along the lines of ‘Make Britain Great Again’. Without the EU, the UK will be richer, stronger and more important. No matter how vague and improbable, this sounded good. Again, we saw a line of reasoning that we recognize from other populist movements. The myth of restoration of lost power was very attractive to the English people. While their away from’s were very specific the Brexiteers towards arguments were very general. There was avery strong element of the metaprogram of change’ here as well.

The towards arguments of the remain camp were more specific. They wanted to basically keep things as they were, and people knew more or less exactly what that was like. Nothing mythical about that. There were no advantages they could offer, that the UK didn’t have already, being in the EU. It was basically a ‘maintenace’ position in meta program terms. Often experienced as safe, but boring.

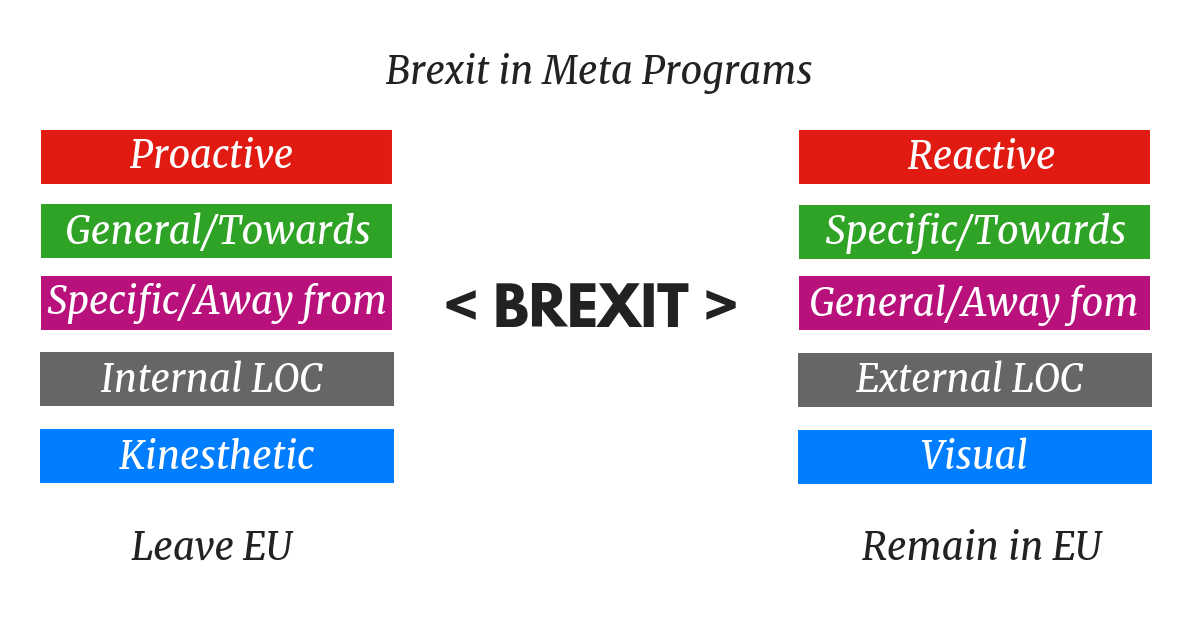

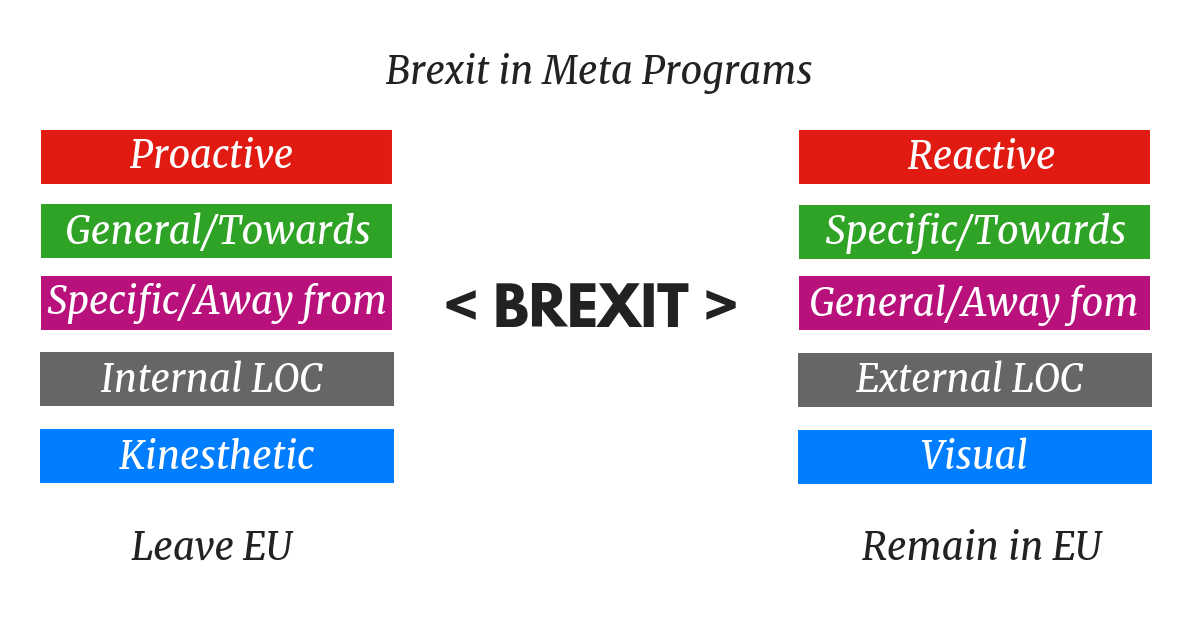

Proactive versus reactive

The leave camp was saying: ‘Let’s leave the EU and be great again’. The remain camp was saying: ‘Wait a minute, let’s first take a good look at all the the consequences this will have’. The remainers were responding to the leave arguments. The leave arguments were setting the scene, framing the discussion. This made the Brexiteers proactive and the remainers reactive, in the sense that they thought about what the other side was saying.

Locus of control

The leave camp was expressing internal locus of control: ‘We have the strength to shape our destiny’. Their main argument was that Britain would regain an internal locus of control that was potentially there but that has been dampened by the EU. While the remain camp took a more external locus of control position. They were saying: ‘We are part of bigger systems that we are dependent on. A lot of global developments are way outside of our control. And if we leave the EU, we’ll lose even what little control we have over that’.

We could dive into all of this more deeply, but I just want to mention one more observation and then sum up the positions. The leave camp seemed to have more kinesthetic arguments, based on gut feelings, pride, fear, irritation. While the stay camp sounded more visual. ‘If we look at the actual numbers’, ‘If we look at the global situation’.

When I sum up the meta programs, this is the picture:

So why did the leave camp win?

- To most people, proactive arguments (‘Lets do it!) sound better that reactive arguments (‘Wait! Let’s think about this’).

- People are generally more motivated by general towards, broad positive goals (‘We will be great!’) than by specific towards, narrow positive goals (‘We will keep our farmer’s subsidies’). Positive goals invite a pleasant emotional state and this state tends to be stronger when the goal is painted in broader strokes.

- Politics is a lot about locus of control. Who has the power? Politicians demonstrating internal locus of control (‘Yes we can!’) tend to be more popular than politicians showing an external locus of control (‘We are dependent on things that are bigger than us’). What the Brexiteers were basically saying is: ‘Let’s feel proud about our power to control things in the future!’ It’s a promise of future internal locus of control. Remain got the emotional benefits without the burden of responsibility. It’s the political version of ‘Buy now, pay later’: ‘Feel the power now, carry the responsibility later’.

- People generally like simple, kinesthetic arguments (‘We are for pride, honour and the welfare of our people’) ‘rather than complicated, more visual arguments describing multiple elements and relationships (‘If we look at international law and our geopolitical position it is clear that we need to think carefully about closing our borders’).

Overseeing these thinking style differences, it is actually surprising that the leave vote wasn’t even bigger…

Populist politicians

I guess the profile I sketched here, this combination of Graves drives and meta programs, is similar for most populist politicians. They claim to represent the common people and to fight the elites on the behalf of them. They are attracting large numbers of voters in most European countries. Brexit was only the beginning of a long series of right wing successes. I am afraid that the more thoughtful, informed, global view will always be more difficult to ‘sell’. It takes a greater mental effort to even understand that position.

Rob Wijnberg, a popular Dutch philosopher and journalist, has commented on this too. He notes how right wing arguments tend to sound simpler and more powerful than left wing arguments. Because the archetypal right wing argument is: ‘This is good for us, let’s do it’. Period. General, proactive, towards statements. While the left wing argument is more like: ‘There is us and then there are all these other people, and we all have our qualities and our rights, so let’s find a just and workable balance’. And also… More specific, reactive statements.

Now what?

So if we know this, then what? We can see the Brexit as a familiar clash between right wing red/orange populists and left wing blue/green reasonable politicians. Psychologically speaking the populist are unfortunately holding the better cards. Which they have had up their sleeves ever since Hitler came to power in the thirties of the last century.

If you don’t like populists, like me and most of my highly educated, cosmopolitan friends, how can you make use of this analysis? I believe that the voice of reason can be more influential than it has been recently. This voice may have a tendency to speak in a reactive, specific, away from, visual manner, but this is no necessity. Reasonable arguments, even though they tend to be more complicated, can be presented in a proactive, general, towards and kinesthetic manner. I believe that reasonable politicians should model the populists in their thinking style and their presentation, if not their values. And understand that thinking style is not the same as thinking content. Meta programs are ways to express, handle and present your values. Blue/green values can be expressed in this format just as well.