When you are reading this, you probably understand that MindSonar is a contextualized measuring system, rather than a standard test. MindSonar measures your mindset in a given context. And we assume that you may have a different mindset in different contexts. I often express this in a simple metaphor: “Give uncle Fred three glasses of whiskey, and he is a different person”. If we compare it with personality tests, MindSonar is more like a thermometer and less like a box of rubber stamps.

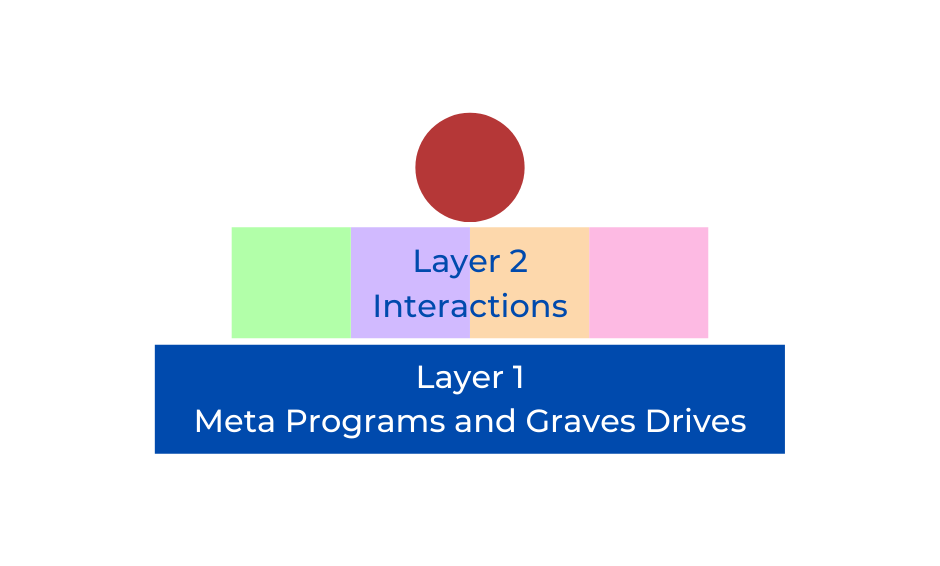

Now that we are mixing metaphors anyway, I would also like to point out that MindSonar is like a layered cake. Let’s have a look at how the layers will be different in different applications of MindSonar.

Layer one is measuring Meta Programs and Graves Drives. Layer two is defining a combination and what that combination does in a given context.

Layer one is always the same: defining the mindset (thinking styles and value types).

Layer two can be different, depending on the purpose we use MindSonar for. In recruiting f.i., we are looking for combinations that work well in a certain context (a job, a role, a set of tasks). This is the benchmark. We then compare candidates with that benchmark. Depending on how big the project is, we may even apply statistics to support our benchmark.

The cherry on the cake is the application, the added value. In this case: selecting a candidate that will do well in that job. Or maybe I should phrase that more carefully: a candidate that has the right mindset for that job.

Like I mentioned before: what the second layer of the cake is made of, depends on what we want to use MindSonar for. In coaching – rather than recruitment – we usually start off with a combination that creates problems in that context for that person. This combination describes how the problem arises. So in coaching, layer two is a problematic, undesirable combination.

The coaching cake has – in this phase – a different cherry too. Here the added value is understanding how the problem arises. In a sense you are baking two cakes here. That second cake, with a different layer on the same basis: the desired thinking patterns and value set for that context. What kind of mindset would this client rather have? What kind of thinking could solve the problem, or even prevent it from arising at all? Often this is a fairly simple formula saying: “More of this and less of that”. “More of this meta program and less of that meta program. More oft his Graves Drive and less of that one”.

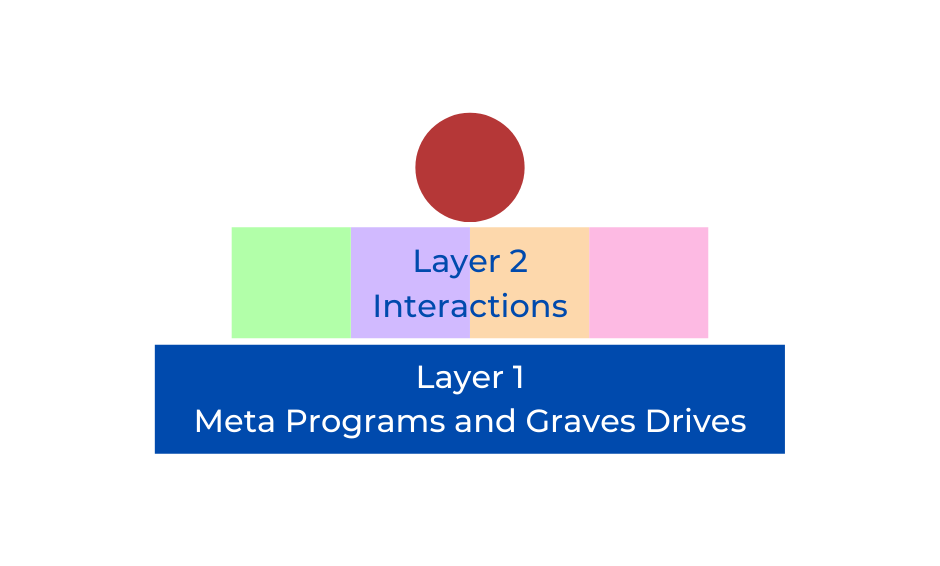

In team building, a third example, the top layer is different again. Now it consists of looking at the interaction. How do the different mindsets of the people in the group influence each other? And how does that explain – or describe – the strengths and challenges of the team?

In team building too, just like in coaching, there are desired and problematic combinations, but now they are mixes, rather that simple combinations. In this case the cherry is not finding the optimal mindset, but rather finding and propagating the optimal interaction of mindsets.

Pro’s and con’s

The good thing about all this is, that you can calibrate MindSonar to the situation you are using it in. MindSonar will be more accurate for that situation than any standard test could be. In a sense you are constructing a new benchmark – however informally – every time you use MindSonar.

There is also a price to pay: you – as the MindSonar professional – will have to determine the benchmark for that context. Usually, of course, you will involve the client in this. It is work you need to do. You will have to mix and bake that second layer, before you can eat the cake. That makes the measurement more relevant and accurate for that context than a standard test. But is is also more work than using a standard test.

An example

To give an example, let’s assume there is a standard test for empathy. I haven’t dived into this, but there is probably a test like that somewhere. It might have a name like NCEES “The North Carolina Emotional Empathy Scale”. Measuring ‘The ability to feel what somebody else feels’.

Now, if I am hiring a group of new coaches for students in my university, I would want them to be reasonably empathic. So I could give candidates for the job this imaginary empathy test, the NCEES. And I might also want to find candidates who are congruent, and persuasive, and dependable, so I could give them tests for these three qualities too. I might end up with a whole bunch of tests, depending on how specific I want to get. This presupposes, by the way, that I have a pretty good idea of what qualities a good student coach has and what tests are available. I might even find a test for coaching ability somewhere, although that would probably not be focused on coaching students, specifically.

The advantage of the standard approach is, that I can start right away. Break out the tests and start measuring! Although, in actual practice, it might still take me quite a lot of reading and evaluating to assemble a good testing kit. But let’s say I have done this before, I know what I want to measure and where to find good tests, so I can do this quickly. In the layered cake metaphor: I can get started without baking the second layer. A time saver. But there is a downside: I don’t know how well my combination of standard tests predicts coaching performance with our students in our university.

Enter MindSonar. I start by baking the second layer of the cake. I identify positive examples; happy and effective student coaches working at my university. I profile them and I calculate their average profile. I discuss this with my positive examples, the effective coaches – whom I now know, since I just profiled them and I probably discussed their profiles with them. Based on my average profile plus the input of my experts, I define a benchmark profile. This is what I use to select candidates. It is more work, but with this benchmark I am much more likely to be measuring something that is relevant for my university. And I have come know several experts, which may also come in handy during the selection process.